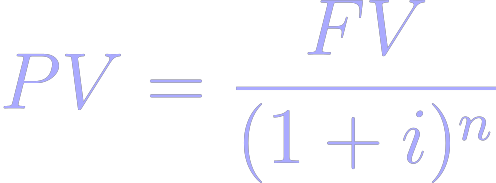

I was asked by a friend, the publisher of the SBInsider, to write 500 words on the effects of inflation on the stock market. I thought it was such a good idea that it would be appropriate to write an expanded version here. There are several factors at play. First, inflation creates market uncertainty, which has a negative effect on the market. Second, inflation tends to make investors somewhat less risk-tolerant, raising the risk premium and depressing prices. Third, it may be that many investors misunderstand how inflation affects nominal dividend growth and continue to count on historical rates without considering the changes caused by inflation. While all these issues have an effect, by far the most significant impact is the result of the Federal Reserve’s attempts to reduce inflation by raising interest rates, by increasing the Fed discount rate. The data suggests that long-term investors holding well-diversified portfolios consisting primarily of value stocks—those with high intrinsic value—may not fare too badly if they hold their investments until long after inflation has returned to ‘normal’, less than two percent. Those investing over shorter terms, in limited portfolios, or in primarily growth stocks—those whose value relies on potential rather than current asset value—are likely to fare much worse. Higher interest rates reduce the future value of any asset that cannot increase in value faster than the inflation penalty. This loss is governed by the present value formula, where PV equals the present value, FV equals the future value, i equals the Fed’s discount rate, and n equals the number of compounding periods in years.

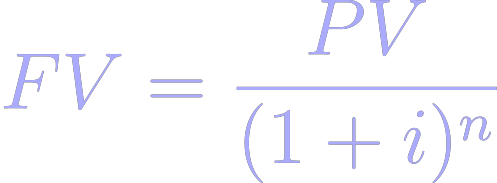

, but when interest rates decrease value, the formula reverses so,

, but when interest rates decrease value, the formula reverses so,  .

.We can create a table of values from one to five years from this formula and see the results.

As you can see, raising the discount rate lowers the future value of an asset. It is not intuitively obvious why higher interest rates lower asset values. There is a balance between the value of money and the value of stuff. Inflation increases the value—price—of stuff while decreasing the value of money. The Fed reverses the balance in its attempt to reverse inflation. It increases the value of money and decreases the value of stuff. In general, stocks, like most assets, are placeholders for stuff and therefore tend to decrease in value when the Fed raises the discount rate. However, over time, the contradicting effects usually balance out and real value is returned. Value stocks in companies with large asset pools see the value of those assets increase in times of inflation and then decrease in times of high interest. In the long run, the balance is restored, and asset value returns to actual value unmanipulated by the economy. Growth stocks often do not have a large asset pool and, therefore, cannot wait out market distortions that may last several years. Growth stocks also suffer from their reliance on future value to make them attractive and support their price with minimal earnings. That is not to suggest that growth stocks are a poor investment only that they do less well in periods of inflation and high discount rates. However, examining the asset underpinnings of growth stocks one holds or is considering purchasing would be well advised. As the risk in any asset increases, the expendability of the money invested should increase in proportion to the risk. Growth stocks are appropriate as part of a well diversified portfolio where other assets protect the investor from the risks associated with them in unstable times. Three of the most translated and read texts ever written give part of the answer. The Bible says, “Ship your grain across the sea; after many days you may receive a return. Invest in seven ventures, yes, in eight; you do not know what disaster may come upon the land” (Ecclesiastes 11:1-2). Shakespeare’s Antonio in Merchant of Venice said it this way, “Believe me, no. I thank my fortune for it —, My ventures are not in one bottom trusted, Nor to one place, nor is my whole estate, Upon the fortune of this present year. Therefore, my merchandise makes me not sad” (Act 1, Scene1). Cervantes’ Sancho gave his answer as, “es parte del sabio guardarse hoy para mañana y no arriesgar todos sus huevos en una canasta” translated to, “’Tis the part of a wise man to keep himself today for tomorrow, and not venture all his eggs in one basket” (Don Quixote, 1615). All these admonitions include the assumption that the world and the market are chaotic places and advise, as a defense against the unknown, diversification. Historically, long-term investors with diversified portfolios have weathered the ups and downs of the market, while shorter-term investors or those with all their eggs in one basket—though occasionally lucky—on average have done far less well. The investor who checks their account balances every day usually loses to the investor who seldom checks their account balances because they know their investments are sound. They lose not only financially but in peace of mind.

If you found this article stimulating, please share it with other folks who might enjoy it. And please share your thoughts below. Dr. Cardell would love to hear from you.

Responses