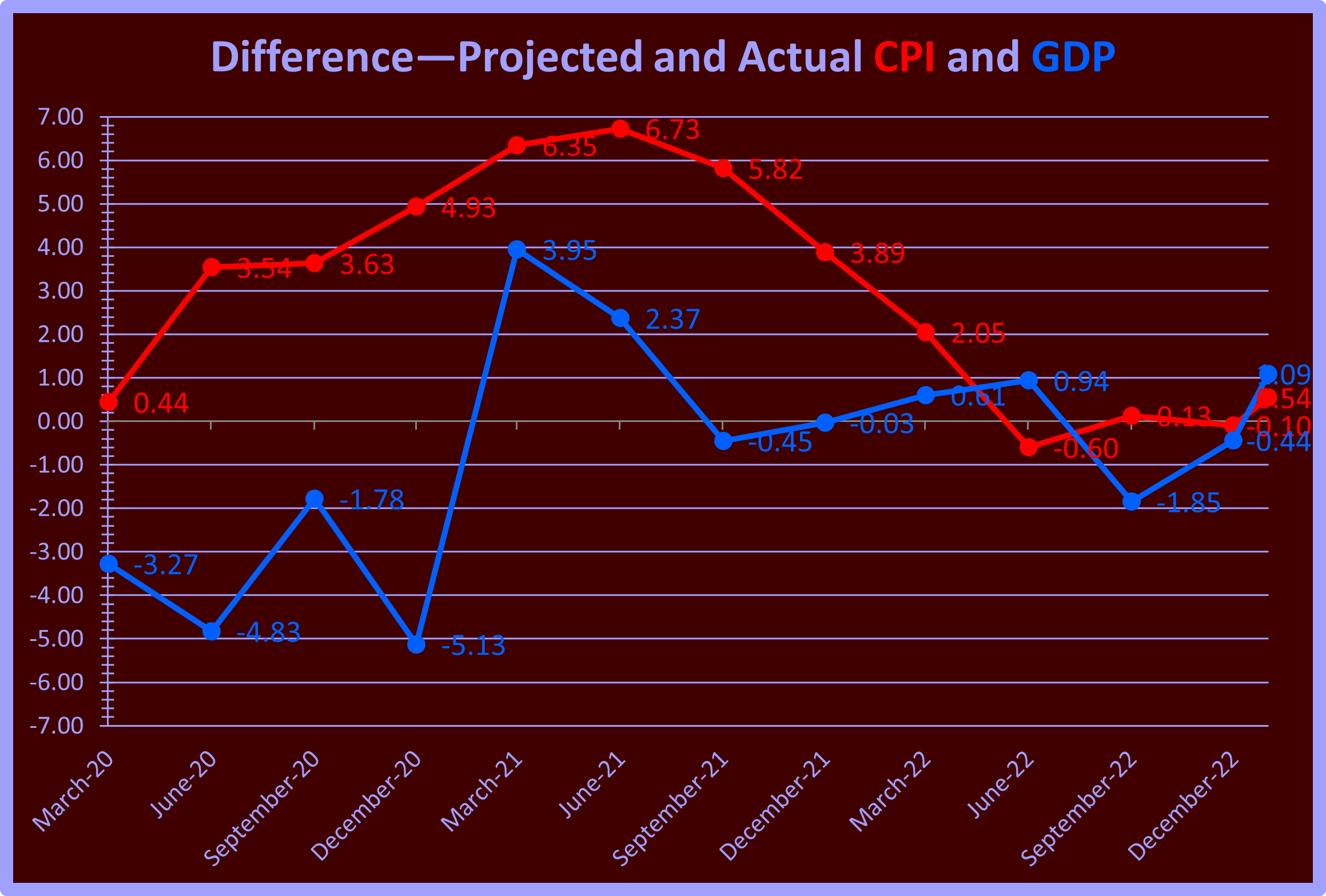

What Is Stagflation? Stagflation, a term that combines stagnation—low economic growth— and inflation, is not just a harmful economic condition but a potentially catastrophic one. It represents a devastating combination of limited economic growth, high inflation, and high unemployment. While a severe supply-side shock, such as the early seventies OPEC oil embargo, can trigger it, the cause is more often unwise economic policies, like high government spending or low interest rates. Stagflation frequently leads to a wage-price spiral when caused by poorly conceived monetary policy. These complex interactions present the Federal Reserve (the Fed) with a particularly vexing problem, as attempting to solve one factor may exacerbate the others. While the most often cited example is the Carter Presidency, it began much earlier. The initial cause was the increased borrowing during the Johnson administration to fund the Vietnam War and the war on poverty. It continued off and on through the Nixon, Ford, and Carter administrations. I was in Washington during the stagflation in early 1971, hired to aide a recently elected Member of Congress who was sworn in that January. I started in mid-February. On my first day, I was walking through a capital corridor and happened to fall in step next to someone who looked familiar. I was walking and reading a policy brief when I saw a group of reporters with cameras and microphones blocking the way. I kept walking and slowed along with the man next to me. A reporter extended a microphone toward the man next to me after saying, "Are you going to 'jawbone' me, Mr. Secretary? As it happened, the man next to me was John Connely, the newly confirmed Secretary of the Treasury. I just stood there, trying to look like I knew what was going on as the Secretary had a brief, informal press conference. Needless to say, my friends and family were astonished that I was on the national news on my first day. The term, jawbone, was Connely's Texas speak for his plan to avoid wage and price controls by persuading companies and unions to voluntarily hold off wage and price increases. The plan didn't work as well as he'd hoped, and the administration ultimately instituted wage and price controls. Stagflation often brings with it harsh measures that are employed in an attempt to control it. Let's examine the current economic landscape. The latest GDP figures reveal a first-quarter 2024 growth of 1.6%, the lowest in two years and one-third below the projections. The inflation rate is 3.5% and rising faster than expected. The unemployment rate is 3.9% and has slowly increased for the past 20 months. These figures indicate more than a potential risk of stagflation, a scenario that could have significant economic implications and should not be taken lightly. The Hanke Misery Index, which measures the effect of the economic picture on real people, is now at 12.5 and rising compared to a nominal 7. How did this happen? In the opening paragraph, I noted that stagflation is usually caused by high government spending or low interest rates. The Biden administration, Congress, and the Fed did both and, in the process, raised the national debt by about six and a half trillion dollars in only three years, by far the largest three-year increase in American history. Adding borrowed money to the economy, which is, of course, what happens when the government then spends it, always increases inflation. The Fed might have been able to mitigate the coming crisis but acted indecisively. Despite inflation beginning in earnest in April 2021, the Fed kept interest rates below 1% until a year later, when it raised them to 2%. Too little, too late. I don't know whether the administration convinced the Fed that borrowing and spending would not increase inflation (remember, they labeled one of their spending bills the Inflation Reduction Act) or if the Fed's projections convinced the administration that their strategy was safe, or they didn't talk to each other. Still, the result was two wrongs, making things even worse. The administration, along with the Congress, are the primary culprits. The reckless spending of borrowed money has always had this sort of effect. However, the Fed bears its share of the blame for its undeserved faith in its economic models. It seems that no matter how often the models are wrong, the Fed continues to act as though they were reliable. My analysis of the Fed's projections of the Real Personal Consumption Expenditures was the bulk of my doctoral dissertation. I found that its projections were correct five months out of 119 tested. I discovered its estimate was within .5%—the functional limit—49 times and inaccurate to the extent that it was useless 76 times. Eight percent of the time, the Fed missed the amount of the move and predicted the move in the wrong direction, up instead of down or the reverse. The Fed was 'right' with sufficiently helpful accuracy only 43% of the time. There is a truism that says the definition of insanity is doing the same thing over and over and expecting different results. Below is a graph of the difference between the Fed's quarterly projections of the Consumer Price Index (CPI) and the Gross Domestic Product (GDP) year-over-year.

Useful projections must be within .5%. As you can see in the graph, the Fed's projections were within this limit three times for both the CPI and the GDP in the past thirteen quarters. They were correct less than one-fourth of the time. Looking at the CPI for June 2021, you can see that their projection missed the mark by almost seven percent. The Fed's average over this period was 2.98% for the CPI, six times beyond the limit of usefulness. It was 2.06% in the case of the GDP, four times the limit. In June 2020, well into the pandemic, when the Fed should have been aware of its effects, the Fed projected that the CPI in June 2021 would be 2.37%, and the actual CPI was 9.1%. While it's fair to say that the Fed couldn't have predicted the Covid pandemic, that's an inherent part of the problem. One of the factors that makes economic predictions problematic are black swans—rare events that do occur. However, the Fed made most of the projections in the graph above after the pandemic had begun, so that shouldn't have been a significant factor. Of course, the real question is whether we are headed for a stagflation scenario right now. The simple answer is that it is just too early to tell. All the key indicators are certainly moving in that direction. As mentioned earlier, the Fed is hamstrung in its ability to prevent the economy from slipping further into a worse situation. Growth will likely continue to slow, inflation may creep up a bit more, and layoffs delayed from the pandemic will likely increase the unemployment rate. The probabilities of at least mild stagflation are better than 50-50, and more severe stagflation is possible. The only long-term way to ensure economic stability is to stop borrowing money and spend less. Having a fixed budget limit would solve the problem permanently. A reasonable and responsible limit to federal spending at ten percent of GDP would solve most of our problems. If implemented today, that would mean setting the spending limit at ten percent of the 2023 GDP or 2.736 trillion dollars instead of the projected 6.5 trillion. I would add an exception for an additional five percent of GDP or 1.368 trillion expressly to pay down the debt from the current 134% of GDP until it reaches twenty-five percent of GDP. At this rate, it would take about 25 years to return the national debt to a healthy level. You know better than to spend 33% more annually than your income, and so should your representatives.

If you found this article stimulating, please share it with other folks who might enjoy it. And please share your thoughts below. Dr. Cardell would love to hear from you.

Responses